Last month, after more than two and a half years of taking all the precautions, my family got COVID. It hit me and my husband the hardest. My kids barely had any symptoms other than runny noses which, let’s face it, when you have a 4 and 7-year-old, their noses are always runny.

I had all the symptoms. Chills, exhaustion, body aches, sore throat, cough, and loss of taste and smell. It was the last symptom that was the most unnerving. I first realized it two days into the illness.

I had all the symptoms. Chills, exhaustion, body aches, sore throat, cough, and loss of taste and smell. It was the last symptom that was the most unnerving. I first realized it two days into the illness.

The first day, I couldn’t even get out of bed, let alone eat anything. The second day, I ventured downstairs to lay on the couch, but wasn’t hungry.

By the third day, I knew I had to eat something so I tried a piece of lightly buttered toast. I don’t know if you’ve ever had toast when you can’t taste it, but it’s pretty gross. It’s like eating a mouthful of sawdust or sand or something equally grainy and unpleasant.

My loss of taste and smell lasted for about two weeks and over that time, after trying to eat many different foods, I thought a lot about food privilege and what a luxury it is to make food choices based on what tastes good.

Everything I loved lost its appeal to me over that two-week time period because I couldn’t taste it, so what was the point? Why eat ice cream if you can’t savor it? I ended up chomping on celery most days because at least that had a somewhat satisfying texture.

Dealing with constant hunger

This strange and unnerving experience made me think about the stories my parents have told me about their childhoods. Both my parents lived through the Chinese Cultural Revolution when Mao Zedong sent the people he deemed to be “intellectuals” to the country to live as peasants in an effort to “re-educate” them.

Families were separated and many people, like my father who was a teenager at the time, were sent to do hard labor in remote villages. In these remote villages, my dad would starve, only having access to things like boiled cabbage, because there wasn’t even cooking oil, let alone meat or protein.

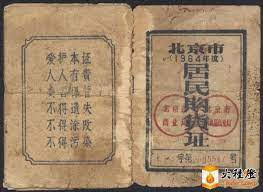

In the bigger cities, where my mom lived, each family was provided a shopping book and a grain book. These books detailed how many people were in the family and how much they have purchased each month.

They were limited on what they could buy, such as approximately one pound of meat, half a pound of cooking oil, and 3.5 ounces of sugar per person, per month.

My mom says because she ate mostly rice and vegetables and very little to no protein, she was always hungry. My parents told me that during the first few years of the 1960s in Henan province, tens of millions of people died of starvation. That was life in China during that time. There was no choice. It was you eat what little you can get, or you don’t eat at all.

Hearing their stories always makes me feel so much gratitude toward my parents because of this life they have given me by immigrating to the U.S. I know I have privilege because I have access to food.

There are three stores that sell groceries within a mile of my home. I don’t ever recall a time in my life where I didn’t have enough to eat. My mom said she still had purchasing/shopping books when I was born in the early 1980s in China.

But supplies weren’t nearly as limited as they were when she was young. Even during our early years in the U.S., when my parents were working multiple jobs as new immigrants and had no money, they always made sure I had enough food to eat, plus a few treats every now and then.

Recognizing our privilege

But what I realize now is, while having access to food is indeed a privilege, it is even more of a privilege to get to choose what we want to eat based on preferences alone. To be able to turn down food simply because we don’t like the taste or texture, or the ingredients, or how close it is to the “best before” date.

To have access to food that we like, and to be able to buy it in bulk, so we can binge whenever we want. To send a steak back at a restaurant because it wasn’t cooked to the temperature we prefer, knowing that it will likely be thrown in the trash while the chef cooks a new one. (Though, to be clear, I would never send food back at a restaurant because I don’t like to inconvenience others for my own gain.)

This experience made me think about food insecurity in this country and in our Kansas City-region. According to Harvesters, 1 in 10 people in the 26-county service area are at risk of hunger and 1 in 7 children are at risk.

The pandemic increased food insecurity significantly in 2020, and the numbers remain at high levels. These are our neighbors who don’t know if there is enough food for tomorrow. They don’t have the luxury of choosing what to eat. They don’t even know if they will eat.

My taste has since returned and I’m grateful. But I’m even more grateful for this perspective that I’ve gained as a result of getting COVID. The first step in creating a more equitable society is to recognize our privilege and then use that privilege to drive meaningful change.

Election Day is right around the corner, so let’s make sure we are electing leaders who not only support programs to help families get access to food, but seek to improve these systems, so they are more equitable for all.

As we head into the holidays, a time of year traditionally filled with gatherings centered around lots of food, let’s remember how fortunate we are to have all that we have, and find ways to give what we can to organizations, like Harvesters that are working to create equitable access to nutritious food.